Waiting Is the New Blocker

Part 1 of 8: The Generalista Capability Expansion Series

Take the free assessment to gain insight into your Generalista journey, and receive regular free learning plans via email.

A decade into my career, I started noticing something about how work actually got done, and it wasn’t the work itself that slowed us down. At Uber, when I needed behavioral data to inform a design decision, I would submit a request to the data science team, and the answer to whether they could do the work would come back three to five days later, if I was lucky, and the answer was often “sorry, we don’t have capacity”.

You see, the data scientists prioritized their work with product managers, and research and design requests sat at the bottom of the queue, no matter how simple the query. At Amplitude, when our design team needed to update the design system with a small component adjustment, a border radius change, or a color token update, the request would wait weeks for prioritization and implementation, even though the actual change could be made in minutes with the right tools, like Cursor.

The bottleneck wasn’t the complexity of the work or the capability of the specialists doing it; it was the dependency structure itself, the waiting, the handoffs, the translation layers between roles that turned simple tasks into multi-week processes.

What I learned across LinkedIn, Uber, and Amplitude is that getting things prioritized was never really about importance or urgency; it was a way for teams to guard resources and control what gets built, which is usually political and not based on business or customer needs. When I wanted to translate research insights into design choices or roadmap decisions at LinkedIn, I had to navigate a political landscape where prioritization meant convincing someone else that my work mattered enough to allocate their time.

At Uber, designers struggled to get their ideas coded so they could accurately communicate their vision and get stakeholders aligned on direction. That translation gap between what a designer could articulate in a static mockup and what users would actually experience in a working interface created endless cycles of miscommunication and rework. The work itself was fast once someone actually did it; the delays came from the architecture of the dependencies we built into our organizations, and the assumption that every discipline needed a specialist to execute even the most basic tasks.

Then something fundamental shifted. AI commoditized baseline execution, making these dependencies optional. What I’ve watched happen across teams at Uber, Amplitude, and now Evisort is that the work itself hasn’t changed, but who can do the baseline versions of that work has expanded dramatically. We’re making it possible for people to do good enough work in adjacent disciplines to unblock themselves on simple tasks that used to require waiting for someone else.

From Sequential Dependency to Parallel Discovery

Traditional product development ran in sequence, and each handoff introduced delay and translation loss. Research would complete a study and write a report; designers would read the report and translate insights into mockups; product managers would translate mockups into requirements; engineers would translate requirements into code; and by the time we shipped, months had passed, and the original insight from research had been filtered through so many interpretations that what we built often missed the point.

At Uber, this process meant that a simple feature could take three months from initial research to validation, not because the work was complex, but because nobody worked in parallel; everyone waited for the previous phase to finish before starting their part. The delays weren’t in the execution; they were in the handoffs, the clarification meetings, the alignment conversations, and the rework cycles when someone discovered that what they thought the previous team meant wasn’t what the previous team actually meant.

What I’ve seen change in the last two years, accelerated dramatically by AI, is that teams can now work in parallel if they’re willing to challenge the assumption that only specialists can do specialist work. When our designers learned to write basic SQL queries, they stopped waiting three days for analytics and started making decisions based on real data pulled in ten minutes. When we started prototyping in code at Uber, the feedback we got from stakeholders changed completely because they were experiencing something real.

More recently, I talked to a researcher at another company who delivers coded prototypes as standard deliverables; she builds games that visualize user behavior patterns or working versions of features that let stakeholders experience what users would experience, and the quality of feedback has completely changed because people aren’t imagining anymore, they’re experiencing.

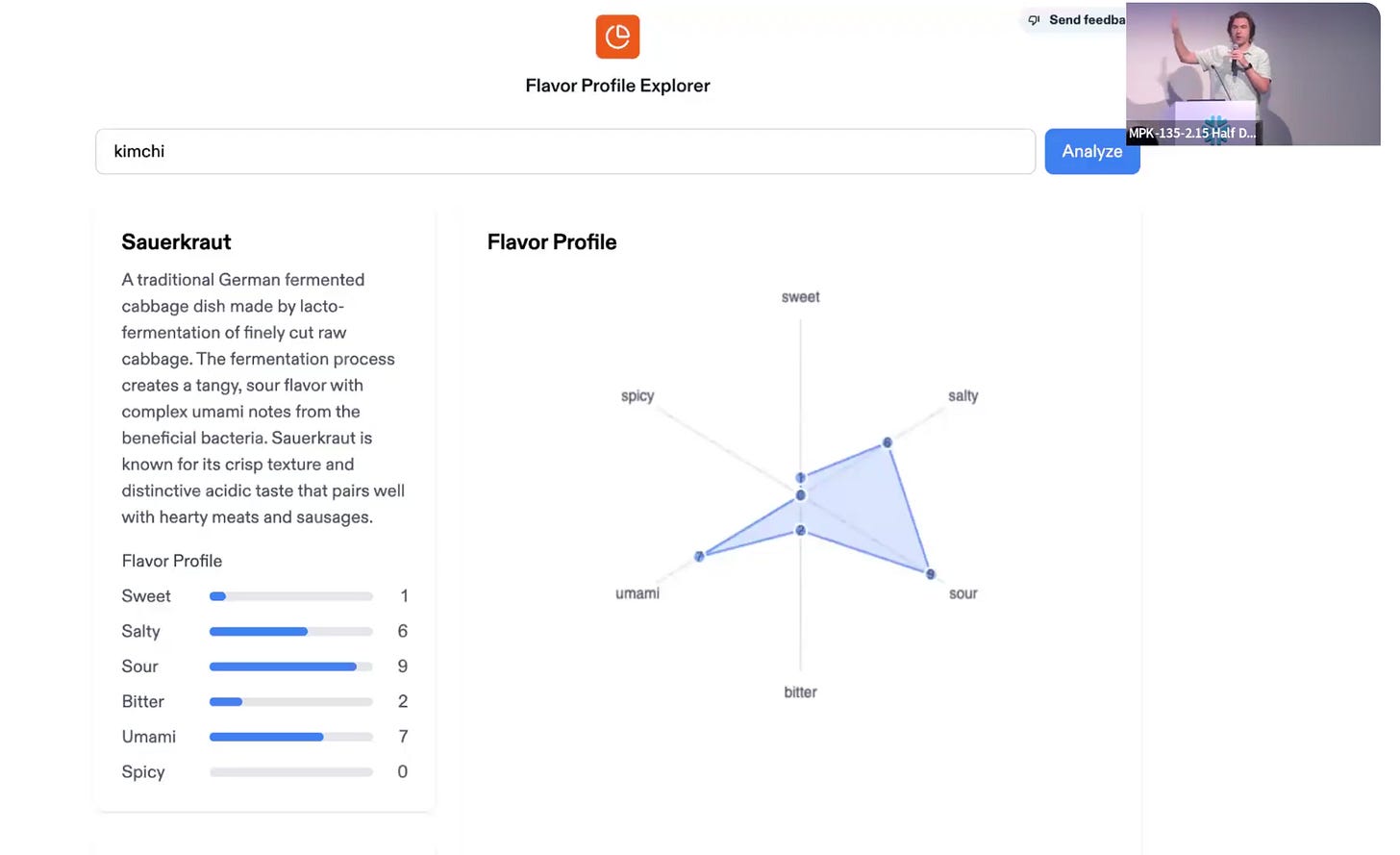

Andy Sybalski, who was an early designer at Google and the design founder for Uber Eats, has been exploring this shift in particularly interesting ways. He talks about using AI to translate between qualitative and quantitative modes, which was extraordinarily difficult five years ago but is now almost trivial. In one example, he demonstrated that he used qualitative assessments like “vibe” to rank cities for conference locations, having the AI generate structured data about how laid-back or tech-focused or outdoorsy different cities feel, then building interfaces that let you filter and compare cities based on subjective criteria that would have been impossible to quantify before. In another example, he extracted the taste elements of kimchi and used AI to find other foods with similar flavor profiles, demonstrating how you can move fluidly between subjective experience and quantifiable data, opening up entirely new design possibilities.

Designers can now build these kinds of tools themselves in hours using AI assistance, where before they would have needed specialized engineering, data science, and potentially machine learning expertise just to test whether the concept was worth pursuing.

What This Means for How We Work

The bottleneck in modern product development is no longer “can we build this?” It’s “should we build this?” and answering that question requires fast iteration, not perfect documentation. A feature idea that used to take six weeks to spec can now be prototyped, tested with users, and either killed or refined in one or two weeks. That compression is only possible when people can do baseline work across disciplines without waiting for specialists to execute every step.

The pushback I’ve encountered, both when building these programs and when expanding my own capabilities, typically centers on quality concerns. People worry that if non-specialists do specialist work, the output will be lower quality and specialists will spend more time fixing bad work than if they had just done it themselves.

This is the same argument that gets made every time capabilities democratize, whether it is user experience research, design, engineering, or any other discipline. What I’ve learned, both from building self-service programs and from the writing I did on democratization of specialization, is that this concern misunderstands what baseline capability expansion actually enables. When a designer writes SQL queries to unblock themselves on simple data questions, they’re not replacing data analysts; they’re freeing data analysts to focus on complex analysis over repetitive queries. When a PM prototypes an interface idea, they’re not replacing designers; they’re giving designers a clearer starting point to refine and elevate.

What does change, and what causes legitimate concern, is that when teams feel threatened by others doing what used to be exclusively their work, they sometimes react by trying to claim ownership of other teams’ outputs in return. I’ve seen this happen when PMs start using AI to create prototypes and then try to push those prototypes as the final design direction. This is a natural organizational response to feeling like your territory is being encroached upon, and it’s part of how teams evolve through this transition.

The response that actually works, the one I’ve learned from both personal experience and from frameworks like William Ury’s “Power of a Positive No,” is not to block but to integrate and guide. When a PM comes to you with an AI-generated prototype pushing their agenda, you don’t say “this isn’t your job, go away”; you take their prototype, review it with respect, unpack the assumptions they made, distill those assumptions into requirements where appropriate, and help them with the next step. This is a variation of Ury’s “Yes, No, Yes” framework: yes to their effort and initiative, no to using vibe-coded prototypes as final direction without design thinking, yes to a collaborative process that leverages what they built while bringing design expertise to refine it.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Adaptation

Not everyone wants to eliminate bottlenecks, and this is the part of the conversation that makes people uncomfortable. Some people prefer waiting because it protects territory, provides cover for lack of progress, or feels safer than learning new skills. I’ve watched talented professionals defend dependency structures that objectively slow them down because those dependencies also insulate them from having to expand beyond their comfort zone, and I understand the impulse even if I think it’s ultimately self-limiting. The market doesn’t care about your comfort zone; it rewards people who deliver impact, and increasingly that means people who can unblock themselves.

The reality I’ve observed across LinkedIn, Uber, Amplitude, and now Evisort is that professionals who eliminate their own blockers advance faster, have more influence, and weather organizational changes better than those who maintain rigid role boundaries. This isn’t because they’re smarter or more talented; it’s because they have more agency, more ability to act, more capacity to demonstrate value. When roles consolidate and organizations restructure, the people who survive and thrive are rarely the most specialized in a single discipline; they’re the ones who can create value across multiple areas and adapt when the environment changes.

What’s Coming Next

Eliminating individual bottlenecks is the foundation, but it unlocks something more significant: the ability for teams to work in parallel, to discover through building, and to test assumptions in days. When everyone on your team can do baseline work across multiple disciplines, the discovery process compresses dramatically because you’re not waiting for sequential handoffs; you’re building rough versions together, seeing what works, and iterating based on real feedback. That collaborative discovery process and how to structure teams and workflows to enable it are what I’ll explore in the next article in this series.

For now, the question isn’t whether you should learn adjacent skills or whether you can afford to expand beyond your specialty. The question is whether you can afford to keep waiting when the barriers to self-service have collapsed, and whether you’re willing to build capability that gives you agency. I spent the first decade of my career navigating organizational structures designed around role specialization and sequential workflows, and I spent the last few years watching those structures become optional as AI made baseline execution accessible to anyone willing to learn. The work is still hard, expertise still matters, and specific roles remain important for complex problems that require deep knowledge and refined judgment.

What changed is that the waiting is now optional, and the people who realize that are the ones shaping what comes next.

Take the free assessment to gain insight into your Generalista journey, and receive regular free learning plans via email.

About: John Garvie is Head of Design at Evisort AI (Workday). He was previously Director of Design at Amplitude and Design Director at Uber, where he was the first UX Researcher to transition into design leadership. He led research for 130M+ users across Uber Eats and Uber for Business, and was one of the first UX Researchers at LinkedIn’s advertising business (now $4.2B). His work focuses on capability expansion, cross-disciplinary collaboration, and building systems that enable teams to discover faster.*

Nicely written! So much to ponder and discuss... Conventional wisdom often claims that only government has these inefficient dependency structures and handoffs - and I am certainly seeing them now in my current role... And interesting to reflect on the qual vs quant data divide now, given the new tools and their accessibility, that our former beleaguered machinations on this seem silly. But I'm in the midst of an implementation utilizing a stacked, rather than waterfall, process, and I'm seeing quite a bit of misalignment that is taxing even the most talented players on the scene. The sheer volume of information and activity is overwhelming and drags on everyone's faith that there will be time to align, that it will all come together once we all get a bit further down our parallel roads... Highly skilled/experienced knowledge workers are already reporting superior efficiencies with AI tools - not the stuff we hear in the news, but the more highly specialized folks who are doing as you say, using these tools to write snippets of code to run analytics on their own data sets, fast-track their own presentation slides, help them mine specialized knowledge databases... I think your overall thesis has been about generalists amplifying their skills with these tools, not specialists. But I see specialists doing their own amplification, too.